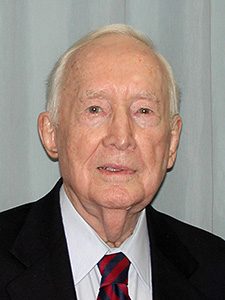

Governor McNair signs Francis Marion College into existence

Francis Marion University was founded on July 1, 1970 through a special piece of legislation signed by Governor Robert McNair. The bill creating the then college, was in response to an overwhelming need for a public education institution in the Pee Dee region of South Carolina.

The university can actually trace its history to 1957 when, at the behest of local Florence citizens, the University of South Carolina established a “freshman center” at the Florence County Library. In 1961, a permanent campus for what was then known as USC-Florence was established seven miles east of Florence on land donated by the Wallace family. That campus is the current location of FMU. Enrollment at USC-F grew steadily, reaching 350 by the mid-1960s. Around that time, community leaders began a movement to establish a four-year institution in Florence.

Francis Marion gained university status in 1992.

Leadership

The institution has had four presidents: Dr. Walter Douglas Smith (1969 to 1983), Dr. Thomas C. Stanton (1983 to 1994), Dr. Lee A. Vickers (1994 to 1999), and Dr. Luther F. Carter (1999 to present).

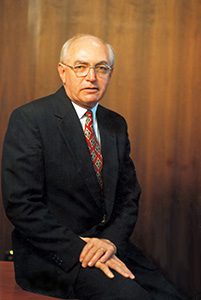

Current President

Dr. Luther F. Carter, longest-serving public university president in South Carolina, brings a rich background to the president’s office. He’s served on the faculties of four universities, as the former director of the South Carolina Budget Control Board, and as a member of the senior staff for two South Carolina governors. Carter, a political scientist, is the author of five books and two dozen juried articles and chapters.

Past Presidents

The Legendary Swamp Fox

Francis Marion University is named after General Francis Marion, a hero of the American Revolution. Marion’s leadership and courage helped keep the flame of rebellion alive in South Carolina during the darkest days of the Revolution, and he is credited by modern historians as one of the great heroes in the crucial southern theater of the war.

Operating out of hard-to-find bases in the marshes and forests of South Carolina’s Pee Dee and Lowcountry regions, Marion and his citizen soldiers frustrated local Tories and their British allies with hit-and-run raids and set piece battles at times and places of Marion’s choosing. Marion’s cunning, and his ability to stay (at least) one step ahead of his foes, earned him his famous sobriquet “the Swamp Fox.” The nickname was not initially awarded as an honor, but soon became a source of pride, especially in the decades following the war.

Marion was not an instant celebrity after the war ended. But as time passed, he was remembered with increasing fondness, and by the middle of the 19th century, had become one of the most renowned heroes of the conflict. Thirty-six U.S. towns or cities, 18 U.S. counties, and 16 townships are named for Marion. Two naval warships have born his name as have four schools, three U.S. lakes, six parks and numerous other attractions and even businesses. Marion is often credited by military historians as one of the “fathers” of guerilla warfare. As such, he is considered part of the official lineage of the U.S. Army’s elite Ranger units.

Some of Marion’s early 19th century acclaim was the product of biographies published at that time that were only loosely connected to the facts of the matter. More scholarly research has been performed in the interim and modern historians generally accord Marion a significant, if often-unappreciated role in the winning of American independence. Historian Sean Busick says simply, “Marion deserves to be remembered as one of the heroes of the War for Independence.”

Numerous legends have sprung up around Marion, and his life continues to be portrayed in some books, on television, and in popular movies without great attention to historical accuracy. This is due in part the relatively sparse historical record which surrounds him. Important details of his life and career are unknown, or remain the subject of scholarly debate.

For example, while historians generally agree he was born around 1732, his precise birthday is unknown. It is certain that he died on Feb. 27, 1795. Consequently, Francis Marion Day is observed as an official holiday in South Carolina on Feb. 27.

Marion was a native of Berkeley County, S.C. His family was in the colony’s planter class, but they were recent immigrants. The Marions were not people of wealth. He was a veteran of frontier fighting in the decades before the Revolution, and was a reading and willing volunteer to the Patriot cause when the Revolution finally came. His leadership in South Carolina, during the war’s pivotal years, was clearly selfless and heroic.

Still, Marion remains a complex, even controversial figure. He had little formal schooling, but became a sophisticated military leader and strategist. He displayed confidence in the men he commanded during the Revolution, giving them an astonishing amount of freedom. And of course, he fought for freedom. That was the Patriot cause. Yet historians all agree that he was a slave owner, both before and after the war.

In that regard, says Marion biographer John Oller, “Marion was a man of his time and place.” Oller goes on to add that, “… and there have been few more trying times and places in American history than from 1780 to 1782 in South Carolina. Marion emerged from that difficult period with a sterling reputation. …”

Marion may have held a more tolerant attitude, for the times, than many of his peers. In his seminal volume South Carolina: A History, historian Walter Edgar notes that that Marion’s partisans were “a ragged band of both black and white volunteers.”

The marker at Marion’s gravesite near Pineville, S.C. may offer the best verdict on the life of a remarkable man whose career may never come fully into view.

“The legend may obscure the Swamp Fox,” the marker reads, “but he reality of what he did has never dimmed.”